Surviving AI just like painters did with photography

The AI revolution has been impossible to ignore over the past few months. There are countless articles and discussions about the “threat” AI could represent for our professions, with dramatic interrogations such as:

- Will AI replace designers?

- Will we lose our jobs?

- Will the whole working landscape be automated?

- Will AI kill creativity?

You’ve undoubtedly already witnessed these kinds of questions in your news feeds. The idea of this article isn’t to address these concerns but rather look at how this disruptive era we’re living in isn’t all that new. History is an endless loop, and it’s exciting to experience this because we weren’t part of something this big before. This revolution strongly echoes the arrival of photography and the upheaval it caused in the world of painting. The good part is that we have the traces of this similar revolution documented (😉) in art history. Can this help us draw inspiration from what’s already happened; so we can better prepare for what’s to come?

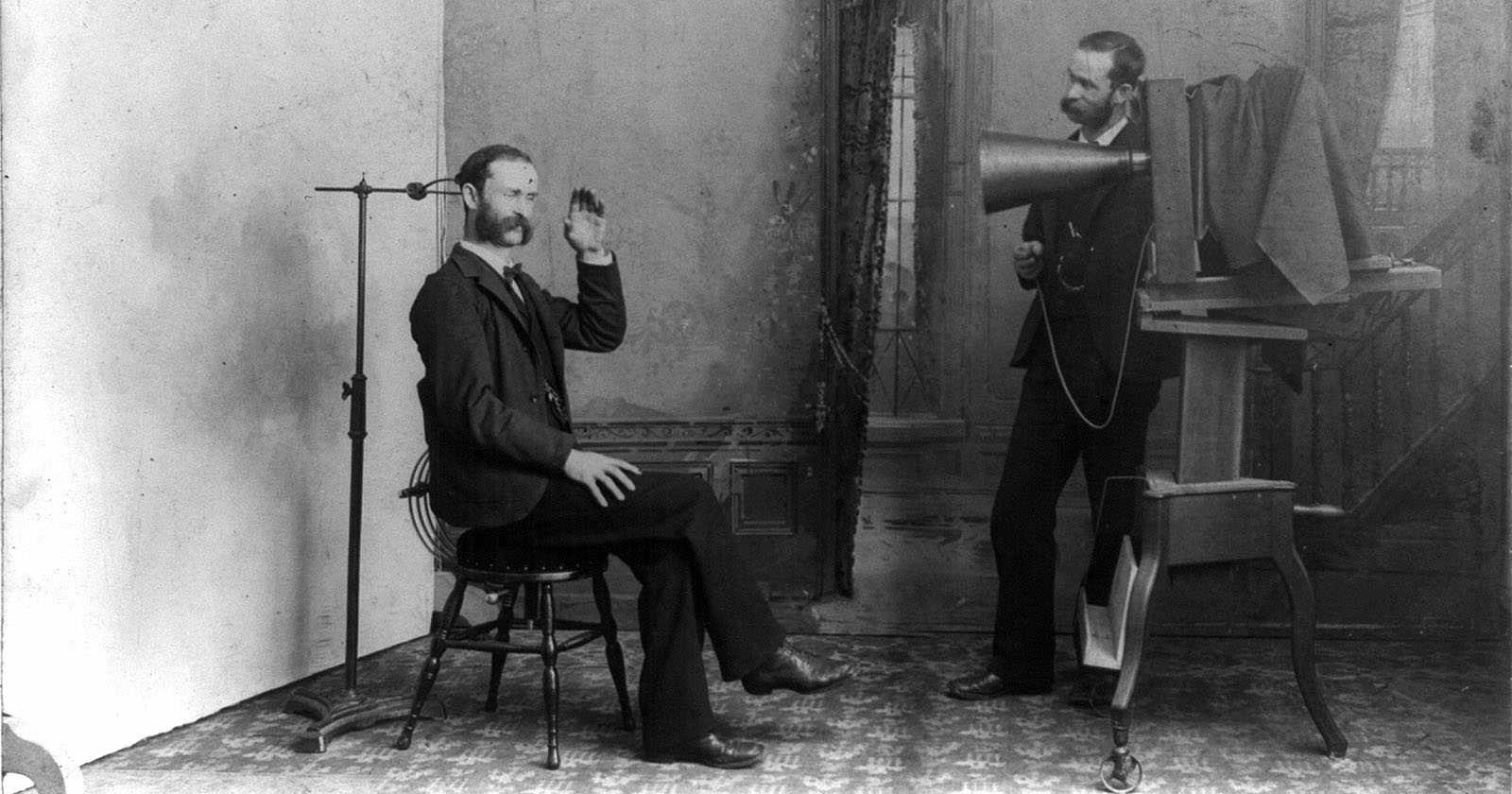

When photography stepped on painting’s toes

Photography arrived in the Western world at the end of the 19th century, clashing with the humming world of painting. Until then, painting had – among other things – assumed the essential mission of representing reality as faithfully as possible (mainly for portraits).

On the other hand, photography inaugurates a new era in representation: we can now have an “objective” representation of reality. We no longer represent reality as we see it and as we the best of our ability. It is now the “reality” that makes an impression on the medium (through the direct action of light (photon) reflected or emitted, from the object to the sensitive surface). In itself, the invention of photography was virtually the result of all the means implemented since the Renaissance to enable artists to find accuracy and copy nature more accurately.

Where painting would take hours and always remain highly subjective in its interpretation of reality, photography does the same job much more quickly, with impeccable objectivity. In fact, isn’t this what we’re trying to do with design systems, to accelerate the process with objectivity?

Design is dead; long live design!

When discovering the first daguerreotypes, painter Paul Delaroche declared, “As of today, painting is dead.” A statement reminiscent of some of the clickbait you’ve probably seen on LinkedIn about AI and design… 😉

With the arrival of photography comes a new profession, that of photographer, and those who practice it are often former painters who converted. Again, we already notice some clever ones rushing in, claiming to be prompt designers or new AI artisans.

Are they the pioneers of these new professions?

What is reality?

However, photography was not initially seen as a work of art. While its emergence strongly influenced art, challenging the truth of the painted image, its main consequence was to make the photographer the translator of objective reality. Still, photography rapidly entered into competition with painting and its painters. At first, it couldn’t be considered an art form, its role being limited to representing reality.

Similarly, things with AI are moving fast. It hasn’t even been a year since this latest AI revolution exploded, and we’re already in a state of upheaval, already pitting humans against machines. Interestingly, the AI era seems to be moving in the opposite direction, making it easier for us to attribute artistic status to its productions, while at the same time doing everything we can to prevent it from bearing witness to our reality. The ChatGPT, Dall-E and Midjourney’s powerful abilities and knowledge make us fear that they, too, are the means of fabricating a very accurate reality. This raises many questions about the spread of fake news, deepfakes and intellectual laziness.

And isn’t it ironic, when we think about the relationship between photography and AI, that it’s an AI-generated image that won the first prize at a photography competition recently?

The AI-generated image that won a photography competition

When photography creates a new reality

However, in reaction to the increasing popularity of photography, painting was forced to question itself and soon reinvented itself. At this point, a proliferation of art movements began to emerge that would be decisive for the evolution of the art form. Painting moved away from the traditional canons of genre and “noble” subjects to focus on the experiences and scenes of everyday life, capturing them in an unexpected light. This led to the emergence of major artistic movements such as Impressionism, Pointillism and, later still, Cubism and abstract art. These movements were purely a reaction to the image revolution of the time, to represent what photography could not. If painters couldn’t rival the precision of portraits and landscapes that a camera could portray, then they would represent the abstract, the spontaneous brushstrokes and all the texture that couldn’t be conveyed in those mechanical realistic photographic shots. Ultimately, photography initiated this search for a new representation of our reality.

Is this a lesson we can learn to prepare ourselves for the AI revolution better?

This is not an Impressionism 4-squared visual generated by Midjourney 😉

Using photography/AI as an ally

Ever since the invention of photography, painters have been seizing on this new technique to free themselves from models and avoid uncomfortable or excessively long posing times, as well as saving themselves a little money by not having to use live models. For example, Cézanne, who was known to be very slow, often used photography not only for his figures but also for his landscapes.

Painters also used photography as a preliminary study of the figure or landscape, from which they drew inspiration in their paintings. Delacroix practiced a great deal in this way, and Millet admits that he uses photographs as notes, but that he would never paint from a photograph; for him, they are merely casts of nature.

By the end of the century, painters such as Eakins, Robinson, James Tissot, Fernand Khnopff and Mucha systematically used photographs as preparatory drawings. The painters Stück and Lenbach even transferred faces for portraits. In the same spirit, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Degas had photographic enlargements made of their drawings, which they then reworked in paint or pastel.

It’s clear that today, we’re using AI to free ourselves from many unpleasant tasks: removing the background from an image, identifying faces, generating visuals, finding inspiration for a poster, and so on. This quest for automation – which we also seek through design systems – always aims to set us free from tedious tasks so that we can focus our efforts elsewhere. Let’s see AI not as a competitor but as a tool to help us daily.

Using photography/AI to create

But while photography has helped painters in their work, it can also be a genuine creative tool in its own right.

Fascinated by photographic technique, the painter Edgar Degas could use his pictorial mastery in his photographic practice and the contributions of photography in some of his paintings.

One of his most famous paintings, “Ballet Dancers in the Wings”, was created using photography. Degas first made three prints to achieve his work, which he combined into an image that became the basis of his work as we know it today.

This is not the only painting Degas made from photographs. The painting “After the Bath” was made using the same technique as the one in which Jules Perrot can be seen. Other works using the same technique followed, and Degas became almost obsessed with photographic technique, to the point of devoting himself to studying lights, shadows, perspectives and other details typical of photography.

Degas was only one of the first of many to use photographs in some of his works. Paul Gauguin also exploited photographic images in some cases, and the painting “Mother and Daughter” is just one example. Also based on photographs, Toulouse-Lautrec’s works such as “The Troupe,” “Jane Avril,” and “Couple in a bar,” are also very interesting. Likewise are Van Gogh’s famous paintings, which he created using characters in photographs as subjects. These include the painting that portrayed his mother and the work in which he portrayed the Belgian painter Eugene Boch.

These are just some of the artists who drew inspiration from the art of photography to create some of their most important works, but painting techniques are still sometimes influenced by photographs.

Similarly, our dear Luke has used Midjourney to create several visuals for his concert posters. Something they documented on their blog explaining the process:

I’ve been using Midjourney to help with prompts, mainly for gig posters, and it’s been glorious. I can generate visual ideas with a super simple idea, and also have the room for happy accidents. I’m still trying to figure out how I feel when it’s really close to the Midjourney stuff and using it relatively wholesale, because, hey I created the prompt that created the picture, so technically I’m not ripping off someone else, but then again, it’s probably pulled from a relatively small pool of sources… I don’t know. Anyway, it’s been pretty cool to play with an inject a bit of life into my scrappy process. Here’s some examples:

But beyond using AI as a new tool for creation, it’s also likely that AI will bring with it an artistic renaissance. Just as photography forced painters to create a style that photography could not represent, the “style” AIs are now generating will likely influence us too. In this ongoing battle between humans and machines, we will look for a way to distinguish ourselves from AIs by creating something they can’t represent. There are already a few leads around the representation of hands, typefaces and the like. And I’m especially eager to see what this will lead to.

Can we survive AI design?

Artists from the 19th-century left a decisive mark in Western painting through diverse styles and techniques. Despite what initially appeared to be the imminent loss of their art and the need to reposition themselves against photographic objectivity, they reaffirmed and consecrated for posterity the “sacred mission” of art, to transcend reality and to inspire aesthetic emotion.

Can we take inspiration from how painters reinvented themselves to create new forms of art and new representations of reality?

Can we live with AI as a powerful tool for our work and a starting point for a new form of creativity? Has AI propelled your creativity or has it freed you from the mundane to focus on more creative endeavors? We’d love to know!