Systems of Exclusion: Design systems and queer exclusion

I was born in Australia way back in the last millenium. I grew up in a suburb of Sydney called Blacktown, about an hour west of the famous landmarks like the Sydney Opera House and the Harbour Bridge. I had a relatively safe middle class upbringing. I played video games, I gave myself concussion riding a skateboard, I had awful taste in music that revolved around nu-metal and cheesy R&B.

Around my teenage years, I started to realise I didn’t feel particularly comfortable in my own skin. The traditional markers of what a boy “should like” never felt natural to me. Sports never stuck with me for more than a couple of years, and I naturally gravitated towards things like softball and netball than I did footy or cricket. I also found myself gravitating towards the groups of girls, much more interested in what they were talking about, rather than the overtly blokey groups, where social interaction usually involved a ball and attempts at competitive violence. Academically, I naturally slipped in and excelled in art, drama, english and food tech, and always struggled with maths and sciences.

Now, I didn’t really care about this. I didn’t care about the ‘what boys should like’ thing, even if it was ten years later that I learnt about the gender binary and how ridiculous it is. I was happy just living my own little existence. But oh lordy did my classmates noticed. It was decided that because I didn’t fit in that mould of what a boy should like, I needed a new label: Gay.

Devastating, right? Well, considering what I know now, not at all, but in the context of the late 90s in Australia, tiny little Luke felt differently. Because this wasn’t just a relatively accurate observation based off of some ill-informed gender stereotypes, but it was thrown at me as an insult. It was their way of saying that I was less than them. That because I didn’t fit into the stereotype of what was “normal” for someone who was male-presenting, I was different. Not different in a good, ‘we are all unique beautiful snowflakes’ way, but as an other. An othering that is rooted in fear of difference. This was the start of an continual internalised homophobia that meant I would refuse to publicly acknowledge my sexuality or gender identity until way later in life. That othering, that started way back then and continued right through to my thirties, caused me to feel uncomfortable enough to closet me and mask my identity as a queer person because of what other people might think.

The other as a concept

Othering relates to the philosophical concept of the ‘Other’, which has popped up since Descartes in the 1500, and can be boiled down to something the opposite of the ‘self’. Not necessarily the literal self, but the concept of self. The self is your internal world. The things you know. Your concept of what a person is, based on who you are. Husserl was the one who applied othering to the concept of intersubjectivity, or the psychological relations we have to other people. It was from here that the concept of the ‘other’ as a radical threat to the existence of the ‘self’ was formed. And it makes sense. The self is what we know. it’s what we understand. The ‘other’ is different. It’s unknown, and therefore a threat.

So with that in mind, the term Othering describes the reductive action of labelling and defining a person as a subaltern — as someone who belongs to the socially subordinate category of the Other. It’s about labelling someone as different from the ‘norm’, and therefore in the margins of society (fun fact, it’s why we have the term ‘marginalized’). And why does society do this? Because it props up the dominant systems that already exist. Labelling something as other is to say that it is lesser than the self in an attempt to diminish personal social status and political power. It’s to displace the othered community so they can only operate in the margins of society.

It’s a concept that is propped up by the binary. And we hecking love binaries. Humans use binaries for everything, because it’s an easy way of identifying what is relatable (ie the plural self) and what isn’t (the other). Male or Female. Straight or Gay. White or Black. Rich or Poor. Able-bodied or Disabled. These are all common binaries that historically carry with them a connotation that one is superior to the other (incorrectly, of course). One is the norm and one is the other. One is the privileged and one is disadvantaged (interestingly, they’re also all things that are in no way binary).

Othering via systems

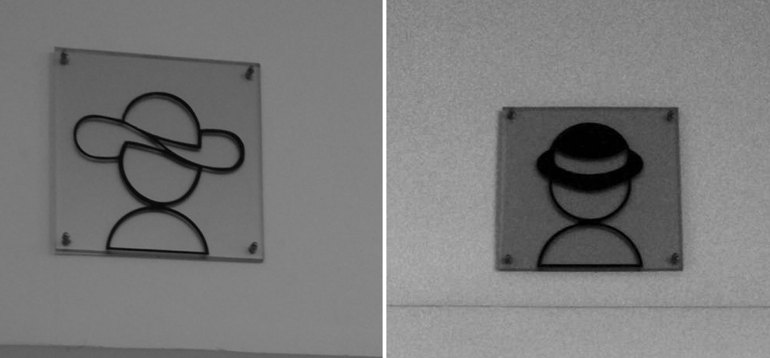

What does all this have to do with design systems? In my teen years, by having insults thrown at me, I was labelled other in a pretty blatant way. But actually, that process of teaching me that I was not ‘normal’ was way deeper than that. And to be honest, what caused those people to throw insults at me was a taught homophobia. A systemic homophobia. Because othering is built into our systems. The language we use – mankind, manpower, chairman, manmade, fellowship, forefathers all assume a dominant, male gender. Man up, run like a girl, wearing the pants in the relationship, boys don’t cry – idioms that reinforce gender stereotypes for no reason. The fact that we still see ‘female’ placed before titles like CEO or lawyer, because we assume the default is male. The way we symbolize things – if you look at a toilet sign, you could assume the two genders are skirt wearing and naked.

And this starts early. Children are branded in pink and blue everything, from clothes, to decor, to toys. Heteronormative friendships between opposite sexes are peppered with talk of marriage, boyfriend and girlfriend, and whether they kiss. And apparently, having a drag queen read stories to children is unnecessarily sexualising children? Honey, we’ve all been doing that for eons. Just that sexualising children by talking about kissing or relationships when they’re three years old plays into existing thoughts about what’s normal. Our world enforces binaries. It enforces exclusion. Even the word ‘heteronormative’ has the word NORMAL in it to denote that one is default and one is other.

These things are systemic. Which is why it’s important to not (always) place the blame or hate on individual people acting within these systems but on the systems themselves. We need to recognise these systems and start to unpick the world we’ve built one stitch at a time.

Where we come in and questioning our roots

As designers, it’s our choice whether we design experiences that support these othering systems or attempt to rewrite them. Especially when we consider that the products we design are more often than not being used by millions of people everyday.

The impact is real!

But before we get into the nitty-gritty, real-world examples of how we can improve our design, we need to go back to basics. And a big part of this is questioning where we came from. We have all built up a ton of knowledge that inform our designs — from the fundamentals of grid systems from Josef Muller Brockman, to the concepts of swiss design of Ernst Keller, to modern digital design principles like Responsive Web Design from Ethan Marcotte, 10 usability heuristics for user interface design from Jakob Neilson, or Atomic Design by Brad Frost. I don’t want to detract from any of these highly influential, and often game changing, foundational concepts and texts, but if we look at almost every major player who has shaped UI and UX design, there are some strong shared characteristics of all of these people: Cis-male, white, able-bodied. That’s not a failing from them as individuals, but it’s important to acknowledge that our foundations come from people with inherent privilege who are informed from a position of power — from the dominant forces in society. Does this mean we should discount what they’ve done? No. But acknowledging this allows us to begin to question our foundations, and make sure we’re not propping up systemic design that Others people.

But Luke, I hear you say, how can a button be homophobic? How does my form field make you feel less of a person?

Exclusionary form fields

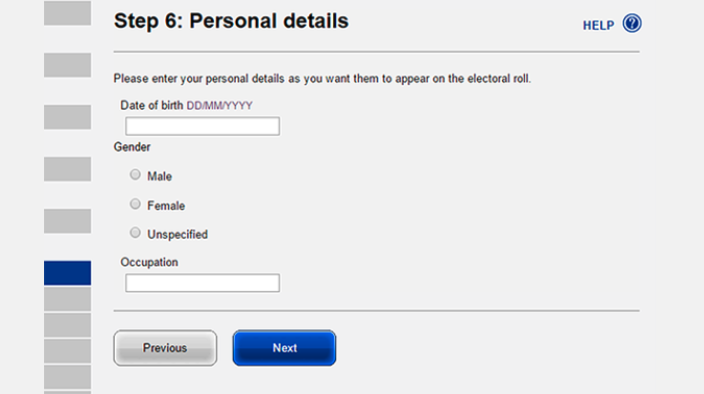

When we dive into it, it’s more about the patterns, guidelines and principles in our systems, than the elements or components themselves. And these usually break down to three main areas of improvement: Language, Defaults and Representation. But how do these show in components? Let’s start with a really nice easy one that almost all products contain: Form fields. More specifically, let’s start with one piece of data that a lot of people want to know: gender.

The gender field

I’m not going to pretend that gender isn’t a controversial topic, but let’s lay out some definitions. Gender is defined as a social construct of norms, behaviors and roles that varies between societies and over time. Gender is often categorized as male, female or other, non-binary terms. Gender identity is one’s own internal sense of self and their gender, whether that is man, woman, neither or both. Unlike gender expression, gender identity is not outwardly visible to others. For some people, gender identity aligns with the sex assigned at birth. For transgender people, gender identity differs in varying degrees from the sex assigned at birth. Gender expression is how a person presents gender outwardly, through behaviour, clothing, voice or other perceived characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine or feminine, although what is considered masculine or feminine changes over time and varies by culture.

In other words, gender is complicated. There are over 80 different common gender identities, and it is a very individual, fluid thing. However, when we represent gender form fields, we usually reduce it to Male and Female. If we’re lucky, there’s a slightly better option that includes ‘Other’.

First off, that binary of male and female can get in the bin. Even if we’re talking about biological sex, sex is not binary. To start with, 1.7% of people in the US are intersex, which means that they are born with a combination of male and female biological traits. While this feels like a small number, it means there are 5.64 million people in the US who this applies to. That’s 1 and a half times the population of Berlin. It’s more than the entire population of Norway. How would your business feel if you were excluding the entirety of New Zealand?

Further to this, studies in the last 5 years are coming out to say that genetically speaking sex is a spectrum anyway, and the markers that we think of as XX or XY are just the start of what makes up our biological sex. So, even if we are talking about biological sex, it’s not that simple anyway.

However, let’s look at that second, slightly better option…

Other.

We’re literally othering anybody who doesn’t identify with that binary of Male and Female. As a non-binary person, this sends me a clear signal: I am not welcome here. And it’s not like this would be a complicated fix to make it leagues more inclusive. ‘Not listed here’ with an optional field. ‘Something else?’ ‘Another gender’ ‘Non-binary’… Yes, by explicitly listing two genders and not the rest, you’re still marking that third option as an Other, but at least you’re not explicitly Othering the person.

But it’s not just the options you provide, it’s also the order you show them in. For some unknown reason, it’s still relatively easy to find forms that place Male before Female, despite F definitely coming before M in the alphabet. I’d love to hear some arguments as to why that aren’t just about making the male default. You could argue that it’s about data, and males make up the majority of the audience, but it’s a weak argument, as there are very few products that are exclusive to a single gender.

The obvious option here is to make gender an open text field, or when we consider good UX, an open text field that autocompletes. But data cleanliness! If we leave it open we’ll get all sorts of things! Someone might identify as a table which would ruin everything. However, in this age of AI and LLMs, even the most unclean data sets can be very easily and simple cleaned up with a quick call to a basic LLM. Even if you want clarity on the data by limiting, grouping into more open categories can happen behind the scenes easily.

Before you do this though, make sure you ask the question of why. Why do you need this information in the first place? Is it important? What is it used for? This usually boils down to two reasons: demographics, personalization, or regulation. If it’s to do with demographics, getting the best representation of your user, and not making reductive assumptions by limiting choice, is going to inform any decisions you make off the back of the data more robust. If it’s to actively alter the experience via personalization, then question whether what you’re doing is an inclusive practice, or are you possibly othering someone who doesn’t fit into the mainstream of that category. If it’s for regulation, then at least surface the question of why. If we don’t question these decisions, they will stay part of the system.

The key takeaway is that if you need to collect gender, make it as inclusive for the user as possible. If you need to clean the data in the backend, you can do that, especially if you consider regulation or legislation that requires it.

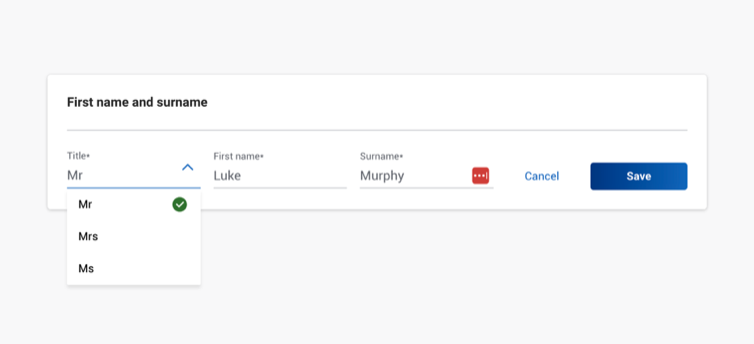

The title field

Now for another minefield: Title.

But it’s just a title. What does that matter? As a non-binary person, every time I have to put Mr down because it’s a required field, I die a little death. This is erasing my identity. It’s telling me that my chosen identity isn’t valid or relevant enough to be provided as an option. Which hurts and marginalizes me.

Also, why do we need titles? Aren’t they outdated? Also, there are so many of them if we want to include all of them, from Mr, Mrs, Ms and Dr, right through to Lord, Her Royal Highness, Sister or Grand Lord Pubar (Ok, I made that last one up). Kudos to anyone that includes all of them, but what a terrible experience it creates. And realistically, how many monarchs do you have using your product? Do we really need a marker to tell us whether you’re married or not (although only if you’re a woman)? What do we use titles for anyway?

Titles. In the bin.

Except…

When I researched this for the episode on trans-exclusion for Amy Hupe’s Systems of Harm, I assumed that yeah, titles are stupid. Get rid of them. However, I was discounting groups of people for my own benefit. I hadn’t thought that a title can be important to a person’s identity, whether it’s a trans person who has fought for their right to be recognised as the gender they’ve always felt, a married woman for whom being married is a key part of their identity, or a woman from a marginalized background who has fought over the odds to become a doctor. Getting rid of the title field would be a subtle way of erasing their identity.

Similar to the gender field, providing an open, non-restrictive way of entering someone’s title is far more effective than providing a rigid set of options.

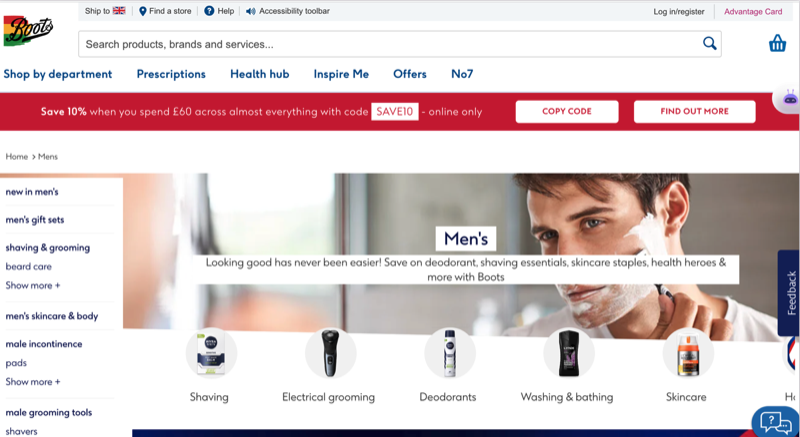

Categorizing based on what you know

It’s not just form fields, either. Categorizing or personalizing your products or services based on an assumed gender is especially prevalent in e-commerce. While it might feel natural, especially in anything that has to do with bodies, it’s also used with completely arbitrary products like toys, books, razors, stationery... The mind boggles.

Because products like this aren’t cut and dry. Even the ones we assume are specific to a particular gender are probably used by loads more folks than you think. It’s not uncommon for women to live in traditionally male clothes. The rise of the ‘boyfriend’ jeans, or stealing your male partner’s clothes is very fashionable. Like putting a label of ‘boyfriend’ on something hides the truth that it’s just women wanting to wear clothes that are categorized as men’s. Personally, I love a good pair of leggings and a cozy jumper in winter, but it’s almost impossible to buy these anywhere other than the ‘women’s’ section on websites. ‘Men’s’ toiletries and skincare seem to be manufactured to smell like childhood locker-room trauma, and so I’ve always used ‘women’s’ toiletries. Is there a difference between them? Aside from the aroma profiles or marketing fluff, no.

And we, as the designers designing the shopfronts that house these products, commonly fall into this binary trap. Most websites delineate between men and women as the two options. We’re starting to see attempts at companies trying to get away from this, which is great, but we still have a way to go to not present everything through a gender binary lens.

You can only be what you see

Why does this matter? A large part of this is about being seen to feel valued. That is, representation. And to give the world it’s credit, diverse representation has been getting a lot better over the last ten or twenty years. Not only are we seeing realistically diverse ranges of people in websites and advertising, but it feels like a consideration in most teams when we design those experiences too. What is important is enshrining this need for diversity at the systems level.

Make sure that representing a diverse range of people is written in your principles and guidelines as a brand and as a product. Not only in your photography, but in your illustrations, copy, form fields, placeholders, avatars… the list is almost endless! Start at the top level principles and work your way down the guidelines for individual concepts, patterns or components. This might feel like a nice-to-have or a luxury that caters to ‘edge cases’. It also might be labelled as an activity that is only being driven by the woke agenda. I’ll let you in on a little secret. These people have always used your product. They have always been here. Not only that, but they make up a statistically significant portion of your user base. It’s only because of representation and ‘normalizing’ that they feel comfortable enough to be seen and heard. The facts are that if you aren’t making your product inclusive from the ground up, someone else will be shortly, and they might take your customers from you.

And while we’re talking about representation, let’s take it to a higher level than principles… Unfortunately, a fair generalization of design systems team is that they are monochromatic and overwhelmingly male. One of the best ways to make sure you have diversity shining through your product and brand is by having diverse voices building your product. Diverse hiring isn’t just a checklist operation, but something that impacts your product by having diverse experiences, cultures and points of view contributing. From the foundation, you’re building your product with a team that better reflects the world that potentially uses it. Ask your recruitment team about their diversity policies, and how they approach diversity in hiring. While I’m a fan of affirmative action in hiring practices (especially in sourcing), I know it’s a controversial and divisive topic, but the least you can do is make sure you’re trying to free your process from as much bias as possible.

Let’s queer the world

All these suggestions for ways to improve the way we design are about questioning our perceived knowledge — questioning and challenging normativity. It’s about looking at we do and asking whether it’s the best way to do things. Are we looking through a lens of inclusivity and intersectionality? There’s another word for this, which is queering. For those who don’t know, queer is a word used to describe something or someone that rejects binarism, normativity, and a lack of intersectionality. Because the reality is that we all live outside of the binary. No person fits neatly into a single box, whether that box is class, gender, race, sexuality, ability, body-type… We each have multiple boxes that help define who we are, and those boxes can grow, shrink, shift or change completely. We are all intersectional beings, and those boxes come with their own sets of understandings, experiences and privileges that help or hinder us in the world. It makes the world more interesting. It makes us more interesting. It means that we all exist on a beautiful multi-coloured spectrum of identity. So when you think about it, restrictive, binary defaults are a bit useless.

Defaults can get in the sea.

The binary can get in the sea.

It’s time to queer our systems and make the things we build a more inclusive place.

Further reading

This is an edited version of a talk that I gave at Hatch, Berlin (which is an amazing conference, by the way), and was influenced, shaped and informed by lots of other folks before me, especially Amy Hupe, who started me thinking about this by inviting me on to her amazing podcast. Here is a short list of the things I would recommend reading, listening to or watching to dive deeper into this topic:

- Systems of Harm – A podcast by Amy Hupe, where she talks to guests about their experiences and takes on different forms of exclusion in the way we build digital products, especially from a systems point of view

- Systems of Systems – a talk from Clarity by Tatiana Mac, where they talk about how the systems we build can’t live in a vacuum, and how they are influenced by the wider societal systems that often discriminate against marginalized people.

- Decolonizing Design Systems – a talk by Michelle Chin from Converge UK 2023 about how we view design systems through the lens of white supremacy, and how we can start to unpick our notions of what design is and make it more inclusive of a global audience.

- Rethinking Gender – a graphic novel by Louie Läuger, looking at different gender identities and gender representations

- Queer: A Graphic History – a graphic novel by Meg-John Baker about the history of queer identities, looking at the thorny parts of LGBTQ+ culture and where we’re going in the future.