5 Tips for writing effective design principles

What are design principles and what’s the point?

When you create your first zeroheight styleguide, one of the first sections we provide in the template is for design principles. This is because your principles should be one of the first things documented when you start on your Design System. However, you should have your design principles sketched out long before you have the need for a fully documented design system. Your design principles are how you, as a design team, define what quality is. They are the foundation for your critiques, and are essential for growing your team in a scalable way.

So, what are design principles? In essence, they are a few statements that cover off the most important things to you as a design team when producing your work. Within orgs, principles often sit at both a company wide level (brand-based), as well as at a function level (like product design, UX researchers or the Design Systems team).

Why are design principles handy? They enable your team to have a guiding light when they’re deciding how they design a particular solution, whether it’s from a UX point of view, or from a visual point of view. This is especially true when onboarding new designers or contractors, as they can effectively act as shorthand do’s and don’ts so a designer can get to work as quickly as possible.

They also act as a guiding point around conversations on whether a design is effective at what it’s trying to do. Say, for example, you have a guiding principles of ‘get the user in and get them out as quick as possible’, but your designer has created a beautifully designed 15 page form to complete a task, your guiding principle provides a good grounding for discussing how that form could be improved.

On the flip side of the above, they come in handy when explaining the reasoning behind design decisions to folks outside of the design org, and can hopefully cut down on repeated conversations or objections from outside the design org.

Tip #1: Talk to the folks inside your organisation

First off – what to include? If you’re writing at a company level, you’re trying to encompass what makes your brand unique. It’s best to work closely with the brand team, the senior leadership and product to make sure that there is consensus of who you are as a brand.

The crux of it is that you want to define what is different to how a designer would normally design. At a product design level, it’s generally a given that you’re wanting to create usable products. Writing this down may be pointless. However, if you’re wanting to make whatever the user is doing a delight, you may have something around creating friction that causes the user to smile.

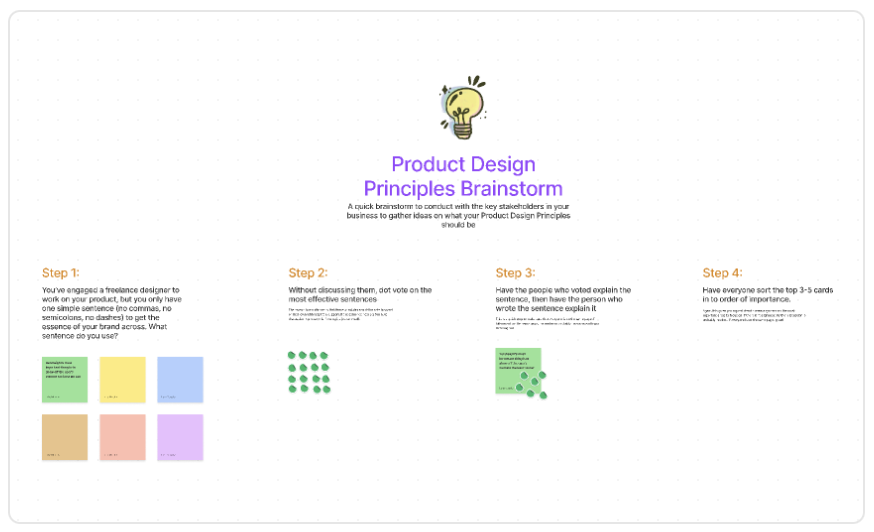

Try this exercise to get some good ideas: Imagine you’re briefing a designer to create something for your company, and you only have one simple sentence (ie. a single-statement sentence with no commas) to give them a direction on the style you’re after. Complete this exercise with multiple people from across the organisation and you should have a good idea of where to start. If you want to give it a go, here’s a quick Figjam template we created for the exercise.

Tip #2: Use research to base them on what your users actually need

Another good source for what your design principles should be are what your users say about you. Talking to your UX Research teams, or poring through the research you’ve conducted can help you discover what Jarod Spool calls ‘emergent design principles‘. These are principles that are based on the current problems your users have when using your product. These are often the most important right now for creating a product that satisfies your user needs, and oftentimes, these are principles that are designed to be phased out once you’ve solved the user need and it’s baked into your product and team. As an example, Jarod uses ‘Polish before new features‘ for a team where the overall product quality isn’t up to scratch. This is great in helping prioritise and push back, when what you need to solve is the ‘death by a 1000 paper cuts‘ problem.

Tip #3: Start with your TL;DR version

In terms of how you write your principles, you should be able to boil it down to a simple TL;DR (too long; didn’t read) statement. At zeroheight, our top principle is ‘Our users’ content always comes first‘. Because we’re effectively a platform for other people’s content, it’s worth pointing out that the user’s content is more important than anything that serves or promotes zeroheight. This means we often default to simple, unadorned design, and fall back on well-known patterns. At a previous company, we had a consumer-focussed, playful brand, so ‘keep it squishy’ was one of our top principles, to remind the designers that we were aiming for a tactile, fun experience that always brought users delight. Because of this, we often tried to push the box on motion and patterns, and wouldn’t always rely on core system UI, because delight often comes with something unexpected.

These three or so statements should be pithy, easily quotable and easy to remember. If folks constantly have to look up what the principles are, they’ve probably failed in how effective they can be.

Tip #4: Add context to avoid ambiguity

Once you’ve got your TL;DR, pithy sentence, it’s time to flesh it out so that the principles can be as helpful as possible. This is where using your describing words can be quite handy. Take the time to write out a good paragraph on what it is that you mean, and what it is that you don’t mean. The idea is that this can be used as a reference when someone isn’t quite sure they’ve understood where the principle is guiding them and add more colour and depth to the pithy one-liner.

Similar to how you would with your components in your Design System, it can also be quite good to include some Do’s and Don’ts. Again, this helps remove some of the ambiguity around the statement. For example, in the ‘keep it squishy‘ principle, we subscribe to the McDonald’s Chicken Nugget rule, where we want it to feel squishy and tactile, but we also want it to be reusable and repeatable, so we have 4-5 variations on most UI elements. Any less than 4 feels same-y, but any more than 5 just feels chaotic.

Finally, if you have them, provide a design hall of inspiration with each principle. Providing examples, with associated critiques, of how this has been put into practice well, and where it’s not been done so well, is a great way to really illustrate what it is you’re trying to get at. One important thing to note – if you’re using live examples, it’s always good to check that whoever designed the ‘bad’ examples are happy with their work being shown in this context…

Tip #5: Define your principles down to the product level

I mentioned earlier that some folks have their design principles set at a brand or company level, and then have more specific principles set at a lower team level. The idea here is that these should cascade down, so that while the top principles still ring true, there are more specific things to keep in mind at a team level. A common instance of this is defining principles at a product design level may include some user-focussed principles that just don’t exist at a brand level. Similarly, an internal tools design team might have completely different goals to an externally focussed team, so may want their own design principles to reflect this.

In terms of how far you go down, having principles for different products makes sense. Going deeper than this, may just lead to cognitive-overload-explosion when a designer needs to keep in mind 15 sets of design principles, or may be a symptom that your top level principles aren’t helping anyone.

Where to go from here

Whether you’re starting out fresh, or revisiting principles you wrote two years ago, it’s always good to look around at how other folks write their design principles. We’ve pulled together some examples of good and bad design principles in another post to help you stand on the shoulders of giants. Alternatively, you could always check out the open source collections over at Design Principles FTW and Design Principles.